Print Is Not Dead!

Paul Pensom on why brands are wise to editorialise

The death of print

Recent history is littered with premature obituaries for formats and technologies. Vinyl records, analogue photography, printed books – all written off by a media so excited by the digital gold rush they fell over themselves to bury what came before. And yet all these things are still with us – thriving in fact. Why should that be?

As art director of Creative Review magazine for over decade I’ve been asked my opinion on the ‘death of print’ countless times, so I’ve had plenty of opportunity to consider this seeming paradox. It’s a real concern for brands wondering where to allocate precious ad spend, and for young designers deciding whether to specialise in digital or so called ‘dead tree media’.

The ultimate question on everyone’s lips could be summarised like this: ‘Am I wise to invest my time or money in a medium that has been bettered in terms of cost, convenience and distribution?’. My answer is an unqualified yes! And in this article I’d like to tell you exactly why.

The efficiency fallacy

First I want to tackle the question of cost effectiveness. Supposing you’re a marketing manager with a budget for promoting your growing retail fashion brand. On the face of it it’s a simple choice: do you spend your money on an email and online ad campaign which may be seen by millions of people worldwide, and which could potentially run the whole year, or do you allocate perhaps five times more on a print magazine that will reach far fewer people, and of which you will probably be out of stock within a month? At this point let me quote Rory Sutherland, the Vice Chairman of Ogilvy & Mather UK. He wrote recently:

“Billions of pounds of advertising expenditure have been shifted from conventional media ... and moved into digital media in a quest for targeted efficiency. If advertising simply works by the conveyance of messages, this would be a sensible thing to do. However, it is beginning to become apparent that not all, perhaps not even most, advertising works this way. It seems that a large part of advertising creates trust and conviction in its audience precisely because it is perceived to be costly. It is the corporate equivalent of a luxury good. Something you buy to prove you have the resources to afford it.”

VOGUE: print editions across multiple regions every month.

This explains why Vogue still delivers fat doorstop editions across multiple regions every month. The brands advertising in Vogue understand that their customers value print precisely because it is perceived as costly and exclusive; after all, digital advertising is a great leveller. You can have the biggest marketing budget in the world, but in an MPU you still have only 300 X 250 pixels to get your message across, the same as every other business.

So does this mean the world’s top brands have no web presence? Of course not. In fact you often find these companies employing a two pronged strategy, similar to the way nation states exert hard and soft power.

Hard power is the exercise of coercion, of bending others to your will. The ultimate hard power is war. To take a current example, China’s annexation of the South China Sea through the establishment of naval bases could exemplify hard power. In advertising, the analogy of hard power might be employed to describe a digital strategy which involves purchasing mailing lists or user profiles to serve ads direct to a targeted audience.

If hard power is the stick, soft power is the carrot. It is the art of building influence through goodwill. To use another Chinese example, look at the millions of dollars put into establishing ‘Confucius Institutes’ – cultural learning centres – throughout Africa. The Institutes provide Chinese language instruction and other teaching services free of charge. China hopes to reap the rewards in the coming decades, through the affection of a generation of African entrepreneurs who gained their first leg up through Chinese generosity.

Soft power then is the expenditure of cultural capital, in the hope of gains to come. In advertising, that could be producing a lavish, limited-run brochure for your best customers, or a magazine centered on your brand’s sphere of interest, available to those who fill in a subscription, thus providing a valuable source of data capture. These items will be seen by vastly fewer people than your online ads reach, but if done right they will generate immeasurably more goodwill, and what’s more, those satisfied customers will tell their friends, which in the age of social media can mean hundreds of people. At this point you can pat yourself on the back; you will have exercised your soft power.

Why magazines? Why now?

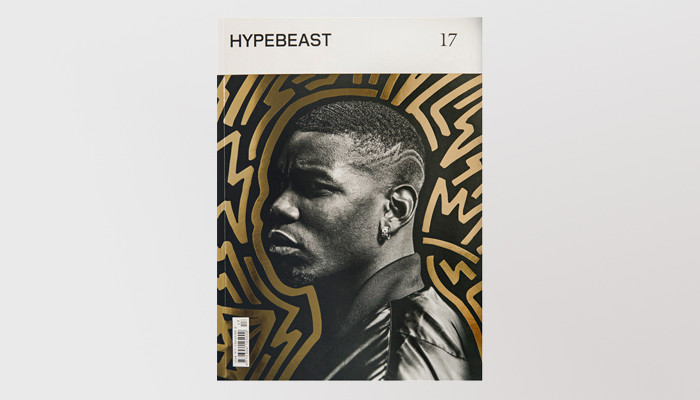

We’ve seen above why it makes no sense to measure print against digital in a like-for-like analysis. Digital media will always win when it comes to mass distribution. Now I’d like to explore why there is a perceived premium to print communication. Is it purely down to cost perception, or is there something more to it? Why do we see successful websites like The Pitchfork Review and Hypebeast, or even multi-billion dollar businesses like AirBnB extend their brands into magazine form? Even a cursory glance at global sales figures for print media make cautionary reading. The graph looks like a downhill ski slope, and a steep one at that. Why on earth would any business want to associate itself with such precipitous decline?

HYPEBEAST: websites moving in to print.

It’s important to grasp that what looks at first like decline is in fact a readjustment, as printed media finds its 21st century niche. It’s what I call the flight of ephemera, a phenomenon that can be observed often when a physical format is challenged by a digital delivery system.

In the 20th century, magazines had many different functions. They carried news, they carried listings, they carried reviews. They were frequent and they were disposable, they were the ephemeral media; today’s headlines = tomorrow’s fish and chip paper.

But then towards the end of the century, the irresistible tug of the internet made itself felt. Time sensitive content could be delivered instantaneously on the web, in every territory across the globe. The first casualties were newspapers, but news sections in magazines quickly became redundant too. The following decades saw giant publishing houses shedding titles as quickly they could, and ‘digital first’ soon became the mantra of the age. But simultaneously, something strange was happening. Whilst the mainstream publishing sector contracted, the independent sector boomed. So much so that we are now living in what magazine commentator Jeremy Leslie calls a new ‘Golden Age’, and he should know; as proprietor of the specialist outlet Magculture, he turns down three times more titles than he has room to stock on the shop’s shelves.

The age of the mass market, million-selling magazine has all but passed. With a few notable exceptions these titles now belong to history. The flight of ephemera has seen these kind of publications find a natural home on the web. What’s left is a global community of small-scale publishers who, far from being threatened by the web, have in fact prospered from it. The internet has made it possible to connect like-minded groups of people as never before, thus allowing specialist titles to thrive that would have struggled to break-even in previous ages.

Magazines no longer lay claim to immediacy then, and this is reflected in both their frequency and their durability. In recent years we’ve seen more and more titles adopt a bi-monthly, quarterly or even annual release schedule. And as issues become less frequent, so they become more substantial. Pagination and paper weight has tended to increase, as have special inks, foils and finishes. These magazines are going to be on your coffee table for some time; they even have ambitions to make it to your bookshelf, so they must earn the privilege.

The tactility premium

This evolution of the magazine’s form points to a basic truth about its survival: that physical media persists because we are tactile creatures. We react tangibly to a rough, mealy textured stock; our fingers savour the contrast between a matte paper and a foil, and linger on the subtle depressions of a debossed logo. We enjoy the heft of a well made magazine in our hands. In contrast with such pleasures the cold unforgiving glass of an iPad comes a very distant second indeed. This is what I call the tactility premium – the advantage that print can buy you. It’s the difference between a potential customer deleting your carefully targeted email over her morning coffee whilst slipping your competitor’s magazine into her bag for later reading.

Paul Pensom is the Creative Director of StudioPensom and the Art Director of Creative Review.